原文網址:https://news.agu.org/press-release/weve-pumped-so-much-groundwater-that-weve-nudged-the-earths-spin

經由從地底抽出地下水並讓它們流到別的地方,光是從1993到2010年人類移動的水量就已經多到讓地球往東傾了80公分左右。這篇新研究發表在《地球物理研究通訊》(Geophysical Research Letters),該期刊為美國地球物理聯盟出版,收錄了地球與太空科學領域具有高影響力的短篇研究。

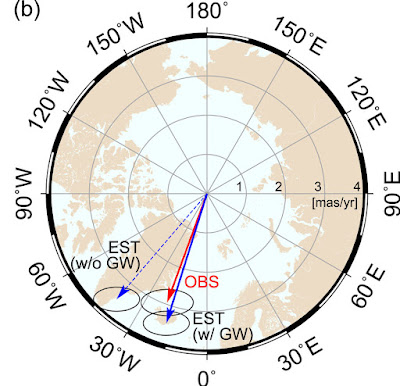

研究人員比較觀測到的極移(紅色箭頭「OBS」)與未包含地下水質量重新分佈的模擬結果(藍色虛線見圖)以及包含進去的結果(藍色實線箭頭)。含有地下水質量重新分佈的模擬更加契合觀測到的極移,使得研究人員了解地下水對於地球自轉影響的程度與方向。圖片來源:Seo et al. (2023), Geophysical Research Letters

根據氣候模型,科學家預估從1993到2010年,人類總共抽出了2.15兆噸的地下水,等於讓海平面上升了6毫米以上,但是要驗證這點卻相當困難。

其中一個方法和地球自轉的極點有關,也就是地球繞著其旋轉的中心點。當地球自轉極的位置和地殼有相對變化時,這樣的移動過程便稱作「極移」(polar

motion)。地球的水如何分布會影響地球的質量分布。就像在旋轉的陀螺上增加一點點重量會讓它晃動,地球自轉也會隨著水移動到各處而出現些微的改變。

「地球的自轉極事實上有很大的變化,」研究主持人Ki-Weon

Seo表示。他是首爾國立大學的地球物理學家。「我們的研究顯示撇除跟氣候有關的成因,影響自轉極漂移最大的便是重新分布的地下水。」

2016年科學家發現水可以改變地球的自轉方式,但是在這篇新研究之前,還沒有人針對地下水探討它對自轉的影響程度。在本研究當中,研究人員模擬了觀測到的地球自轉極漂移以及水的移動。首先他們只考慮冰層以及冰河的影響,接著再把地下水重新分布的不同情境加進去。

唯有在模型中有2.15兆噸的地下水重新分布的情況下,模擬結果才會符合觀測到的旋轉極漂移。如果沒有加入地下水的影響,模型會跟觀測值相差78.5公分,相當於每年相差4.3公分。

「發現旋轉極漂移的原因中,之前尚未釐清的一項讓我相當開心,」Seo表示。「另一方面,身為一位地球公民及父親,看到抽取地下水也會造成海平面上升則讓我驚訝且擔心。」

「這篇研究貢獻良多,肯定會成為很重要的文獻,」並未參與此研究的Surendra

Adhikari表示。Adhikari是NASA噴射推進實驗室的研究科學家,他在2016年發表了水的重新分布會影響地球旋轉極漂移的論文。「他們定量了抽取地下水對於極移的影響程度,這真的意義重大。」

抽取地下水的地點決定了它能對極漂移造成多少變化,把中緯度地區的水重新分配對旋轉極造成的影響更加嚴重。在研究期間,有最多水重新分配的地方位於北美西部與印度西北,兩者都是處在中緯度地區。

理論上,如果各國(尤其是位居敏感地區的)試著減緩地下水乾枯的速率,就可以改變漂移速率,但Seo說前提是這類節約措施要維持數十年。

正常來說在一年之內旋轉極就會移動數公尺,因此抽取地下水造成的變化並不會危及季節如何更迭。但是Adhikari表示,以地質時間尺度來看,極漂移確實能影響氣候。

這項研究的下一步是探討過去發生的事情。

「觀察地球旋轉極的變化能讓我們以大陸為單位了解地下水儲量的變動,」Seo表示。「極移的數據最早可以追溯到19世紀晚期。因此我們有機會利用這些數據來了解過去100年各個大陸的地下水儲量如何變動。是否有任何的水文情勢變化是因為氣候暖化所導致?答案或許就在極移當中。」

We’ve pumped so much groundwater that

we’ve nudged the Earth’s spin

By pumping water out of the ground and

moving it elsewhere, humans have shifted such a large mass of water that the

Earth tilted nearly 80 centimeters (31.5 inches) east between 1993 and 2010

alone, according to a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters, AGU’s journal for short-format,

high-impact research with implications spanning the Earth and space sciences.

Based on climate models, scientists previously

estimated humans pumped 2,150 gigatons of groundwater, equivalent to more than

6 millimeters (0.24 inches) of sea level rise, from 1993 to 2010. But

validating that estimate is difficult.

One approach lies with the Earth’s rotational pole,

which is the point around which the planet rotates. It moves during a process

called polar motion, which is when the position of the Earth’s rotational pole

varies relative to the crust. The distribution of water on the planet affects

how mass is distributed. Like adding a tiny bit of weight to a spinning top,

the Earth spins a little differently as water is moved around.

“Earth’s rotational pole actually changes a lot,”

said Ki-Weon Seo, a geophysicist at Seoul National University who led the

study. “Our study shows that among climate-related causes, the redistribution

of groundwater actually has the largest impact on the drift of the rotational

pole.”

Water’s ability to change the Earth’s rotation was

discovered in 2016, and until now, the specific contribution of groundwater to

these rotational changes was unexplored. In the new study, researchers modeled

the observed changes in the drift of Earth’s rotational pole and the movement

of water — first, with only ice sheets and glaciers considered, and then adding

in different scenarios of groundwater redistribution.

The model only matched the observed polar drift once

the researchers included 2150 gigatons of groundwater redistribution. Without

it, the model was off by 78.5 centimeters (31 inches), or 4.3 centimeters (1.7

inches) of drift per year.

“I’m very glad to find the unexplained cause of the

rotation pole drift,” Seo said. “On the other hand, as a resident of Earth and

a father, I’m concerned and surprised to see that pumping groundwater is

another source of sea-level rise.”

“This is a nice contribution and an important

documentation for sure,” said Surendra Adhikari, a research scientist at the

Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was not involved in this study. Adhikari

published the 2016 paper on water redistribution impacting rotational drift.

“They’ve quantified the role of groundwater pumping on polar motion, and it’s

pretty significant.”

The location of the groundwater matters for how much

it could change polar drift; redistributing water from the midlatitudes has a

larger impact on the rotational pole. During the study period, the most water

was redistributed in western North America and northwestern India, both at

midlatitudes.

Countries’ attempts to slow groundwater depletion

rates, especially in those sensitive regions, could theoretically alter the

change in drift, but only if such conservation approaches are sustained for

decades, Seo said.

The rotational pole normally changes by several

meters within about a year, so changes due to groundwater pumping don’t run the

risk of shifting seasons. But on geologic time scales, polar drift can have an

impact on climate, Adhikari said.

The next step for this research could be looking to

the past.

“Observing changes in Earth’s rotational pole is

useful for understanding continent-scale water storage variations,” Seo said.

“Polar motion data are available from as early as the late 19th century. So, we

can potentially use those data to understand continental water storage

variations during the last 100 years. Were there any hydrological regime

changes resulting from the warming climate? Polar motion could hold the

answer.”

原始論文:Ki‐Weon Seo,

Dongryeol Ryu, Jooyoung Eom, Taewhan Jeon, Jae‐Seung Kim, Kookhyoun Youm, Jianli

Chen, Clark R. Wilson. Drift of Earth's Pole Confirms Groundwater

Depletion as a Significant Contributor to Global Sea Level Rise 1993–2010. Geophysical

Research Letters, 2023; 50 (12) DOI: 10.1029/2023GL103509

引用自:American Geophysical Union. "We've pumped

so much groundwater that we've nudged Earth's spin.”

沒有留言:

張貼留言